Hollywood and Vine

by Tad Friend - THE NEW YORKER

If you haven’t watched YouTube in a while—if you’ve joined the Amish, or you’re Edward Snowden—a lot has changed. Early on, the platform was a salmagundi of out-of-focus lifecasts. The viral hits were cats getting wet and one-offs like “Charlie Bit My Finger—Again!,” a 2007 video whose exposé of House of Atreus-style family strife has earned it more than eight hundred million views. (Spoiler alert: a baby bites his brother’s finger.) YouTube was adults with camcorders shooting kids being adorably themselves. It was amateur hour.

If you haven’t watched YouTube in a while—if you’ve joined the Amish, or you’re Edward Snowden—a lot has changed. Early on, the platform was a salmagundi of out-of-focus lifecasts. The viral hits were cats getting wet and one-offs like “Charlie Bit My Finger—Again!,” a 2007 video whose exposé of House of Atreus-style family strife has earned it more than eight hundred million views. (Spoiler alert: a baby bites his brother’s finger.) YouTube was adults with camcorders shooting kids being adorably themselves. It was amateur hour.

Nowadays, YouTube is almost alarmingly professional. It has millions of channels devoted to personalities and products, which are often aggregated into “verticals” containing similar content. The most popular videos are filmed by teen-agers and twentysomethings who use Red Epic cameras and three-point lighting to shoot themselves. And the platform’s stars behave in ways that are contingent upon a camera. For instance, they act. One of YouTube’s most visible shows—currently featured in magazine and subway-car ads everywhere—is an action series called “Video Game High School” that would be right at home on MTV.

So it wasn’t entirely surprising that some of the most eager participants at this summer’s VidCon, a conference celebrating YouTube, were those who’d been displaced from the platform’s dynamics: adults. Indeed, the conference felt like a May-December romance. Onstage at the Anaheim Convention Center, as the proceedings began, sat Jeffrey Katzenberg, the sixty-three-year-old C.E.O. of DreamWorks Animation. In the audience were more than a thousand middle-aged spectators—producers, agents, ad execs—as entranced as Katzenberg was by YouTube’s smorgasbord of “snackable content.” With the platform’s users watching more than six billion hours of video a month, and people consuming more than nine times as much digital video as they did in 2010, Hollywood planned to secure its own future by consummating a merger. Last year, DreamWorks bought AwesomenessTV, a company that manages YouTube stars, for thirty-three million dollars, and a wave of old-media investment followed.

Sitting opposite Katzenberg, in the role of the skeptical father of the bride, was the thirty-four-year-old Hank Green, one of VidCon’s founders. Green, a fierce advocate for YouTube’s singers, comedians, and “vloggers” (video bloggers), wondered aloud whether YouTubers, most of whom yearn for Hollywood’s embrace, wouldn’t be wiser to shrink from it. “You have everything we don’t have, which is resources and money and expertise and connections,” he reminded Katzenberg. “You, obviously, if you wanted to, could just be like”—he swept his arm sideways and made a crushing sound.

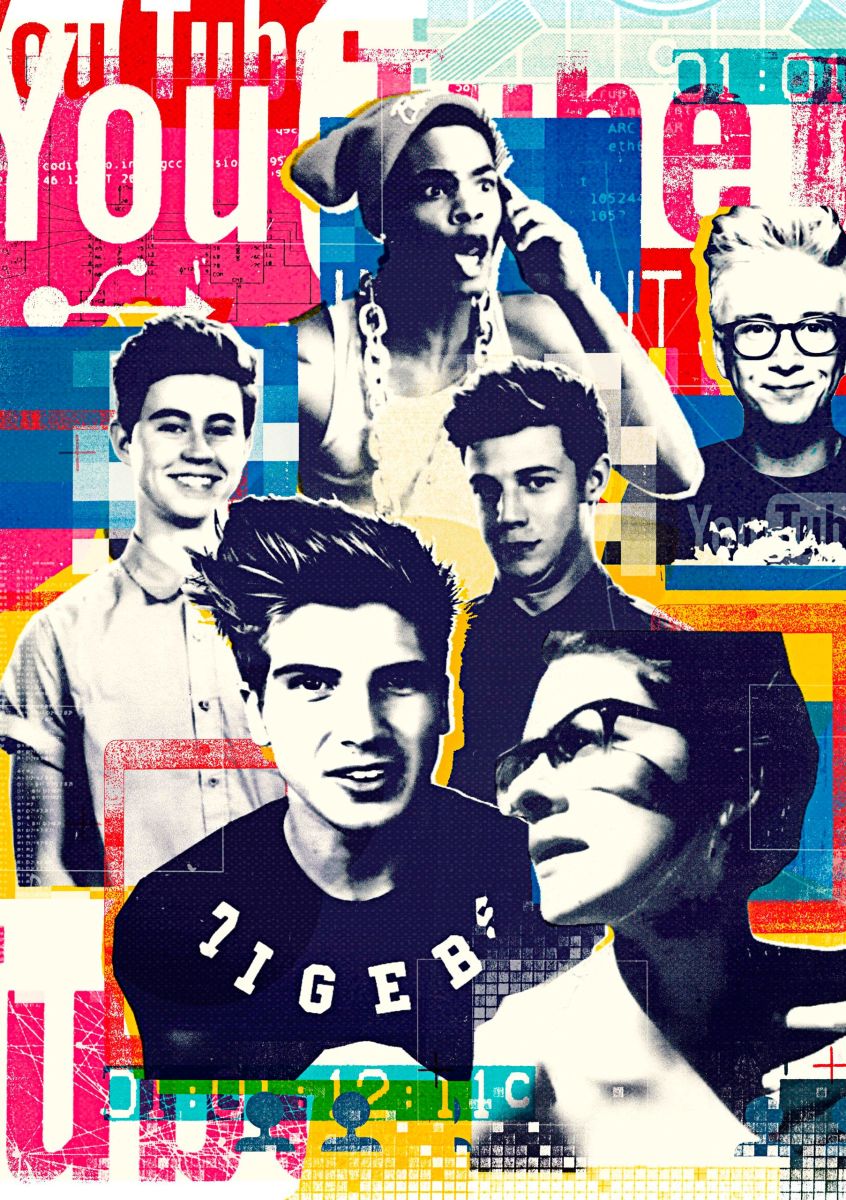

Katzenberg, professing his sincerity, said that he simply wanted to be a “great lighthouse” beaming out helpful links and new verticals to orient those lost in this teeming sea. But his musings were swiftly silenced by a prolonged roar from outside the building—the rest of VidCon’s nineteen thousand attendees, mostly teen-age girls who’d come not to monetize but to adore. The clamor was for Tyler Oakley, an impish YouTube personality with brightly dyed hair whose passion for gay rights, suicide prevention, fast food, One Direction, Lady Gaga, and pretty much everything else exemplifies the platform’s all-embracing ethos. “I’m glad I had security,” Oakley said afterward, “because everyone was trying to touch my hair.” Oakley’s was only the first “bomb rush” of the three-day conference, as attendees swarmed anyone hidden by bodyguards, fangirled at the VidCon prom, and scouted for wizards on the Quidditch pitch. More than nine hundred YouTube channels have at least a million subscribers, so every passing Australian prankster pack evoked Beatlemania. Even unknown buskers inspired squeals and selfies: as in Pascal’s wager, little was lost if the singers turned out not to be stars, and—who knows?—maybe they’d be stars tomorrow.

Because people can watch whatever they want whenever they want on their phones, digital platforms reveal what tweens and teens really like. Thematically, the rebellion is pretty traditional: they like hearing that their feelings rule and that the adult world is an epic fail. It’s the formats that are new; instead of finding reassurance in scripted soaps like “Dawson’s Creek,” they find it in unscripted homilies from charismatic kids and curated images of idiocy.

Devotees of the digital brand Break surf channels that include “All the Animals,” “Heartwarming,” “Pranks & Fails,” “Bizarre & Amazing,” and, of course, “Gaming.” Girls love YouTube’s beauty tutorials and boys love its “Let’s Play” videos, where you follow along as someone plays video games. The platform’s biggest star is a Swedish gamer who goes by PewDiePie and live-snarks as he battles mutants or navigates the virtual reality of Dinotown. “Oh, God, now he’s eating my beautiful face!” he cries, upon meeting a Carnotaurus. “I bet I was delicious!” PewDiePie has thirty-two million subscribers and earns four million dollars a year.

Like punk and piercings and paintball before them, these videos seem to have been designed expressly to blow parental minds. Adults focus on the brevity. Noting that most of the popular material on YouTube is between two and seven minutes long, Ynon Kreiz, the president of Maker Studios—a leading multichannel network, or M.C.N., which aggregates channels to increase their ad revenues—told me, “I’m not sure the millennial generation has the patience to watch twelve, thirteen episodes of an hour-long show—even a half-hour show.”

Kids focus on the community. Digital stars are always in your pocket, always available for oversharing; because the viewing experience is so handheld and interstitial, it feels less like vegging with “NCIS” than like carrying around a newborn puppy. The viewing relationship is bilateral—digital stars take fans’ programming ideas and regularly answer their questions—and its promise is “I’m just like you.” Stardom used to be predicated on a mystique derived from scarcity; you don’t really know much about George Clooney. Now it’s predicated on a familiarity derived from ubiquity. As the teen-age beauty vlogger Bethany Mota exclaimed at VidCon, referring to her legion of subscribers, “I never thought I would have over six million best friends that are all around the world!”

Robert Kyncl, the global head of business and content at YouTube, told me, “People who grew up in an age of connected phones and cameras everywhere are self-aware at all times—they can’t escape it.” Digital stars look like Larry King’s grandkids: they have large heads, wide eyes, great teeth, and active hands, and they never blink or pause for breath lest they lose your attention. A chatty race of manga people, they stream their lives across multiple YouTube channels (one for outtakes and B-roll, one for live gaming, one for podcasts, etc.) as well as over Tumblr, Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook, with merch available on each. Traditional entertainers call themselves actors or writers or directors or the “Blue’s Clues” guy. Digital talents, who often do all of the above—who learn Final Cut Pro and Photoshop from YouTube videos—call themselves “creators” or “influencers.” They don’t have to respond to executives’ notes or depend on a marketing division in Burbank. They just have to be radiant, humble, and terrific. The singer Meghan Tonjes introduced her set on VidCon’s main stage by calling out, “I love you all very much,” but it went without saying. YouTube, with its culture of D.I.Y. meets B.F.F., is how a generation admires itself.

“Within five years, YouTube will be the biggest media platform of any, by far, in the entire world,” Katzenberg told me. But the digital realm is no country for old men; younger, fleeter forms and stars are emerging faster and faster, and you almost can’t trust anyone over thirteen to understand them. YouTube’s primacy as the place teen-agers go after school is already being challenged, especially by Vine, an app of looping six-second videos that launched last year. AwesomenessTV’s biggest stars are the teen-age Viners Cam and Nash: Cameron Dallas and his friend Nash Grier, a rascal with antifreeze-blue eyes who, at sixteen, has ten million followers. Rob Fishman, the co-founder of Niche, a branding firm that connects Viners with advertisers, noted that, after only a few months on Vine, an unshaved account manager at his company “has more viewership than the New York Times has circulation.” Freddie Wong, a twenty-nine-year-old director who co-created “Video Game High School,” told me, “This world, even to me, is so vast and nuanced and incomprehensible it’s like the blind man feeling the elephant—a giant merry-go-round of teens chasing someone who’s famous for making six-second videos.”

While most of the top American YouTubers have moved to Los Angeles, the entertainment capital of the world, most of the top Viners launch their attacks on fame from the city’s newest crossroads: Andrew Bachelor’s living room. Bachelor, known to his friends as Bach and to his nine million Vine followers as KingBach, is a rubber-faced, Gumby-limbed twenty-six-year-old who bestrides the sidewalks of his Hollywood neighborhood in shower shoes, wearing a putatively cat-themed T-shirt emblazoned “Love All Pussy.” He was born in Toronto to a family of Jamaican heritage, grew up in West Palm Beach, and headed to Hollywood as fast as he could. “I knew since third grade I wanted to be Jim Carrey,” he told me. “His freedom, his goofiness, his crazy, loud, sudden energy. I told my family I was going to be a pediatrician, but in the back of my mind I was like, Nope, I’m going to be the biggest movie star ever. ‘Andrew Bachelor’: you say my name, and in every state, every city, every household it brings happiness.”

He lives in a large building for rising young professionals that stands, by auspicious chance, at the corner of Hollywood and Vine. Four other top Viners live in the same complex, and a dozen more within five miles. The building’s lobby and hallways, its pool and Jacuzzi serve as the backdrop for dozens of comedy Vines, and Bach’s living room is like the false-fronted Main Street on the Fox lot. Its centerpiece is a Samsung flat-screen; other decorative touches include a putting green, a Jamaican drum, several pairs of Air Jordan sneakers, an overflowing box of costumes, a bong, and a sprig of mistletoe still taped to the ceiling from a video he shot two Christmases back.

On a warm July afternoon, Bach stood in his living room with two collaborators: Marcus Johns, a twenty-one-year-old free spirit who was the first Viner to reach a million followers, and Armaniche DaSilva, a shy aspiring actor. DaSilva was driving for Uber when he picked up Bach, started chatting with him, and got invited over to work on the day’s Vines. He told me, “This is by far the most important Vining thing I’ve ever done.”

They began rehearsing a Vine where Johns would introduce his friend Bach to DaSilva as “Andrew,” and Bach would be furious that Johns hadn’t used his Vine name. “Should you be executed at the end, because I’m so mad? I stab you to death?” Bach wondered. As he grabbed a retractable stage dagger, which appears in a surprising number of his Vines, the doorbell rang, and eight other Viners streamed in—a few he’d called the day before and their eager friends. These “collabs” fuel creativity, cross-pollinate followers, and reinforce the top Viners’ status—the cartel of the coolest. Bach bro-hugged everyone and abandoned the first Vine for a complex scenario he planned to shoot by the pool.

Bach was introduced to Vining last May by his friend Brittany Furlan, whose own career illustrated Vine’s transformative power. Until last year, Furlan survived by selling yard-sale tchotchkes on eBay; now, as a Viner with 7.9 million followers, she is paid as much as twenty thousand dollars whenever she makes a branded Vine for companies like Trident. Before Bach discovered Vine, his zenith as an actor was getting part of his head into the background of a “Burn Notice” episode. He’d tried YouTube, but it required a modicum of technical expertise, as well as sincerity and a crusading mind-set; if YouTube was for student-council types who wanted everyone to divest from Sodastream, Vine was the sniggering truant who gave you a noogie as he raced by.

Bach concluded that Vine’s comedy vertical—by far its most popular format, although the app also inspires lots of music samples, sports clips, news reports, and stop-motion animation—was made for class clowns like him. Everyone danced with strangers; parodied pop songs, often while driving; had fun with escalators; had fun with supermarket-checkout conveyor belts; had fun with women’s wigs; and got stink eye from old folks. The six-second limit didn’t leave time to do much more than establish a scenario and then undercut it: in Rudy Mancuso’s popular “Swag,” shot at Bach’s pool, Mancuso struts and lip-synchs to the Bee Gees’ “Stayin’ Alive,” all natty narcissism—then runs into a glass door.

Many of the most distinctive bits came from Jérôme Jarre, an ingenuous Frenchman with an arresting smile. In one, Jarre, wearing a fur hat with flaps, wonders, “Why is everybody afraid of love?” Then he creeps up behind an older woman at a Home Depot and terrifies her by yelling “Love!” The Vine gains in power from the looping repetition: you watch it once for Jarre’s wide-eyed expression, once for his Pepé Le Pew accent, once for his hat, once for the woman’s hand-to-heart fright, once to figure out what she was buying (a lamp?), and once for the cathartic timing. A Vine’s blink-quick transience, combined with its endless looping, simultaneously squeezes time and stretches it. In “Gummy Money,” a Viner named Nicholas Megalis proffers a handful of gummy worms as he raps, “Yo, my name is Nicholas / And this is ridiculous / Got mad gummy money / and it is deliciousness.” It loops perfectly, each ending setting up the next beginning, the experience the visual equivalent of opening a bag of potato chips, where you surface in a crumb-basted haze and wonder where they all went.

The three guys who launched Vine, in January, 2013, intended it as a lifecasting tool: I took a walk and saw this. Six seconds seemed long enough to capture a milieu and a mood without risking boredom; as Rus Yusupov, one of the founders, noted, “Nobody’s going to complain that you wasted six seconds of their time.” But Vine didn’t really take off until April, 2013, when it introduced a front-facing camera for selfies: it turned out that people would rather broadcast themselves than their surroundings. Within months, the platform was overrun by Nash Grier and an army of bare-chested fifteen- and sixteen-year-old boys making “teacher be like” jokes. Vine became a kind of mobile, social MTV, with a soundtrack of hits to rock out to or mock, and with kids as the stars. (It was “Beavis and Butthead” all over again, except everyone was better-looking.) And the platform became more predictable. Marcus Johns told me, “Kids are used to the entertainment form of reality, the single-camera style of a totally exuberant person on ‘The Real World’ or ‘Keeping Up with the Kardashians.’ Stereotypes and reliability is Key No. 1.”

For most of its comedy practitioners, Vine is not storytelling but gesturing: it’s part prank, part graffiti. Bach treats it as an ultra-compressed sketch show, one that would do for him what “In Living Color” did for Jim Carrey. His form of total exuberance is playing KingBach, who sports an Afro pick and a thick gold chain and comes on to or goes off on every girl he meets (when one blabs on and on, he sprays pesticide in her face). “KingBach is a fake thug,” Bach explained. “He’s a guy who wants to be initiated into a gang, but who’s actually sort of likable. He says ‘nigga’ a lot and calls a girl a ‘bitch’ in every Vine, where I’d be terrified to do that to a real woman.” Bach excelled at threading in popular memes that, like a high-frequency noise device aimed at young loiterers, only teen-agers would apprehend: the “Selfie” song; calling your girlfriend “bae”; doing the Shmoney dance. And he stretched the boundaries of the form with rapid cuts and a (relative) fusillade of dialogue, pushing a haiku toward a limerick. Soon he was gaining tens of thousands of followers a day, and the exposure helped him land recurring roles on shows on MTV2, Adult Swim, Showtime, and Fox. Whenever he appeared on air, he’d make a Vine that showed the clip playing on his TV set and then panned to him, wearing just shorts or a towel as he wriggled spasmodically, doing his “I’m on TV” dance.

At the apartment, Bach explained the new Vine: Marcus Johns would grab one of Bach’s Air Jordans, or J’s, off his foot and toss it toward the pool—where a trio of Bach’s friends would take rapid-fire turns throwing themselves in, sacrificing their bodies to keep the shoe aloft in a basketball-style three-man weave. They’d end up dead, because, as the joke goes, black people can’t swim. Bach added that the actors who jumped in should wear basketball togs. He offered a set to Jerry Purpdrank, who recoiled: “You didn’t tell me there was water involved!” Bach turned to Alphonso McAuley, who was already backing away, and pleaded, “Alphonso, come on, now! I got towels! I’ll tag you first!” Viners credit their actors and directors by “tagging” them, with hyperlinks to their Vine accounts below the video. “It’s gonna be a big Vine, man!”

“I need to see towels in hand,” McAuley replied. “I need to see Egyptian cotton.”

Bach sighed and pushed into the throng, which parted before him as everyone became very busy with his phone. As the preproduction of the Vine began to resemble a Vine, Marcus Johns laughed and said, “Everyone looks at us like these pioneers, like we know exactly what we’re doing. We have no idea what we’re doing.”

A common sight at VidCon was sharp-eyed men chatting about this digital world they hoped to grasp and shape—a world of “future proofing” and “snacky, listicle, hashtaggy sorts of bits” and “global mobilized ubiquitous pre-roll things.” These conversations were declamatory yet anxious—what app from the diseased mind of a tween savant would disrupt everything next? And were these new stars really, you know, stars?

A few days earlier, Joey Graceffa, who created and starred in a YouTube series called “Storytellers,” ten-minute episodes about gothic doings among high-school hotties (a series that was originally crowdfunded on Kickstarter), met with some financiers to discuss their underwriting a second season. To demonstrate the pent-up demand, Graceffa tweeted “Who wants #StorytellersSeasonTwo? Let’s get it trending!=D.” Within seconds, according to Brent Weinstein, the head of digital media at United Talent Agency, who was at the meeting, Twitter exploded with responses: “It looked like code running down the screen on ‘The Matrix.’ ” Minutes later, Graceffa’s hashtag was the top-trending topic worldwide.

And yet the buyers held off; they weren’t quite sure. An executive at a large cable network told me, “We have a lot of conversations about YouTube. We ask, ‘Is it to us now what cable was to broadcast in 1992?’ The parallels are there—lower production values; smaller, narrower audience—and it’s even cheaper, even more niche, even less profitable today than cable was then. Only”—he hesitated, not quite ready to change his frame of reference—“none of YouTube’s stars have really crossed over and landed a big show on Bravo or MTV.”

But digital feels like the future. Big media companies couldn’t buy YouTube, which has long belonged to Google, and they couldn’t buy most of the individual creators, who’d already been signed by multichannel networks. (They couldn’t even buy Vine, which had been acquired by Twitter; software-based companies were much quicker to see the promise of video.) So, to at least be hedged on this digital thing before it was too late, they started snapping up the M.C.N.s, which had begun styling themselves “next-generation media companies.” Once DreamWorks Animation bought AwesomenessTV, Disney bought Maker Studios for five hundred million dollars; Otter Media, a joint venture of A. T. & T. and the Chernin Group, bought a majority stake in Fullscreen for more than two hundred million; and the European broadcasting group RTL bought most of StyleHaul for a hundred and seven million.

As Michael Green, the chairman of an M.C.N. called Collective Digital Studio, said, “The play is that billions of dollars in TV advertising is going away—everybody zaps past the ads, and kids don’t watch TV anymore—and we all have our hands out, waiting for it.” This idea makes intuitive sense, and, indeed, Nielsen reports that, while people over sixty-five watch about forty-seven hours of television a week, most teens watch only about nineteen. Yet the payoff may be slow in coming: young adults still watch more than five times as much TV as online video, and TV advertising is actually growing much faster than digital-video advertising. YouTube will make an estimated $3.4 billion this year from advertising—but CBS alone earned $8.8 billion in ad revenues last year. Thus far, few, if any, of the M.C.N.s have made a profit.

Digital promotion remains a gray area, where the distinction between shout-outs and brand solicitation and bought-and-paid-for ads can be hard for viewers to parse. The savviest new-media advertiser is Taco Bell. Nick Tran, who until recently was the brand’s head of social media, explains that they “started hanging out with Tyler Oakley, and just like in any friendship he exposed us to other YouTubers.” (Oakley calls himself a genuine “friend” of Taco Bell—but acknowledges that he receives goods and services for his companionship.) Tran continued, “When we partnered with Sony to launch PlayStation 4, we invited thirty or forty YouTube stars to our headquarters to play it before it came out, and to enjoy some new items on our menu—and fifteen to twenty of them vlogged about it.” He shrugged modestly. “People assume that a traditional endorser has a paid relationship—there’s no way to tell if Tiger Woods really loved Buick. But the audience expects that if the YouTube community are talking up Taco Bell it’s because they really love it.”

If a piece of branded content seems funny or cool, as when G.E. launched Marcus Johns and Jérôme Jarre into zero gravity, fans see it not as a sellout but as a validation. Straight selling often flops. Brittany Furlan says that when Wendy’s hired her to make a Vine about its new flatbread sandwich the chain insisted “that I just be seen eating the sandwich, talking about it, and hashtagging it. It got their name out there, all right, but people were saying, ‘Now I specifically won’t go to Wendy’s.’ ”

This balance is particularly tricky on Vine, where there aren’t any pre-roll ads—where there’s no structural way to separate the ad from the content. Because companies can’t cordon off their messages from the messenger, many will associate only with “clean” Viners—ones who don’t curse or inflame. When Bach shot a Vine in his apartment with Oscar Miranda, Miranda asked Bach to dismiss him not as a “bitch” but as a “mitch.” “I can’t have cursing—it messes with my brand deals,” he explained, referring to Vines that he’s made for Toyota and T-Mobile. “That’s gay,” Bach replied, and Miranda spread his hands apologetically.

Many advertisers miss the familiar waters of old media. Brent Weinstein, the U.T.A. agent, explains, “On the Internet, there’s the perception of infinite content to sell against”—advertisers worry that their ads will vanish into the remoter reaches of the teeming sea. He noted that Google Preferred, which places ads against top YouTube videos, was designed to create urgency by creating scarcity: “They sold it by saying, ‘While quantities are still available.’ ” In September, YouTube announced a program that it had quietly initiated months earlier: it would fund its creators’ best ideas—everything from dramas and talk shows to snacky, listicle, hashtaggy sorts of bits—in return for a piece of the shows’ off-YouTube revenues. And in October the company revealed that it was considering a paid subscription service. To bring in premium ads, YouTube had to underwrite real shows—if not “Game of Thrones,” then at least “Storytellers.” It had to become an élitist network as well as a populist platform. It had to become more like Hollywood.

Andrew Bachelor’s actors and crew lounged around the pool, elaborately casual. They routinely flouted the apartment complex’s ban on filming, but today the building manager was patrolling the area. As they waited for an elderly couple to finish their labored laps, Marcus Johns, who was now wearing an Apple power cord as a headband, said, “I follow a hundred and eighty-two Viners—way more than most big Viners do.” When a Viner named Klarity added, “I follow like a hundred and forty,” Bach deadpanned, “But you’re not a big Viner, bro,” and everyone went “Oooh!” In the heavily male club of comedy Viners, popularity is currency; a Viner in Bach’s building introduced himself to me as “Curtis Lepore, 5.3 million followers on Vine.” Adding a million followers is like bench-pressing another twenty-five pounds. Better still, it enables you to charge advertisers about five thousand dollars more for a branded Vine, and makes you that much more likely to catch a producer’s eye. Brittany Furlan told me, “All the Vine stars don’t want to get stuck there. We want to transcend to TV and movies—even though, ironically, we have more viewership than they do.”

When the couple finally emerged from the water, Johns high-fived them. Then he and Bach stood by a bar alongside the pool and surreptitiously shot the first scene. It took about a second: Johns said, “Screw your J’s!,” grabbed the pre-loosened sneaker from Bach’s foot, then flung it toward the pool. As Bach planned the subsequent images—Klarity seeing the sneaker fly by and pushing aside a friend, played by Armaniche DaSilva, to dive toward the pool; the acrobatics over the pool as they kept the shoe aloft; the moment when Bach, amazed, gets his shoe flung back—there was extensive discussion of continuity, framing, motivation, and not “crossing the line,” or jumbling the characters’ spatial relationships. The protocols were those of a film set, yet all they had was a four-ounce iPhone. It was a notable contrast to YouTube, which recently bestowed upon its Los Angeles-based creators a forty-one-thousand-square-foot studio with seven sound stages.

Between setups, Johns asked Bach, “How many J Vines have you done?”

“Enough to get a meeting with Jordan today,” Bach said, grinning; later that week, he signed on to do a promotional video for the sneakers.

The idea for this Vine, complete with product placement, had come to Bach the day before, as a response to something that the Viner Jason Nash said: that Vine, because of its extreme concision and its youthful demographic, inclined to “the worst kind of stereotypes.” Nash explained, “Most of what’s popular is how dumb girls are, or throwing fried chicken into a pool and the black guys want to dive in after it but they can’t, because black guys can’t swim.” Bach thought this observation over, then said, “I’d take it to the next level.”

Bach likes to interrogate stereotypes. In a Vine called “Getting Out of Situations Using the Race Card,” when he’s stopped by a white cop while carrying a clearly stolen TV, he indignantly responds, “What, a black man can’t have a TV?,” forcing the cop to acknowledge, “No, you can be black and have a TV.” At the same time, KingBach is pure shuck and jive. Bach explained, “That’s because, when I tried out the ideas going around Hollywood—that Asians play the smart people, white people play the rich ones, blacks are the thugs—those Vines got the most likes. So it’s not Hollywood being racist—it’s Hollywood understanding what people want to see.”

Klarity, a clean Viner whose real name is Greg Davis, Jr., told me that he and Bach regularly argue this question. Klarity points out that the Vine that gave Bach his catchphrase was neither blue nor racial: a woman gets mugged, and Bach, instead of giving chase, runs up a wall and springs off it backward. When she complains, he gives the camera a sly look and crows, “But that backflip, tho!” Yet Klarity acknowledges that one of his own biggest Vines was “Racist A.T.M.,” in which the cash machine tells him, “Sorry, nigger—you broke.”

Crassness may be inherent in a form that inclines to swift transgression. In July, YouTube’s Tyler Oakley took note of an old Vine in which Nash Grier showed a commercial for an oral H.I.V. test which said that getting tested wasn’t “a gay thing,” then yelled at the camera, “Yes, it is—fag!” On Twitter, Oakley argued that Grier’s stereotyping was “extremely dangerous.” Though Grier apologized on Twitter for having been “young, ignorant, stupid, and in a bad place,” the emerging pattern was that YouTube punctured the stereotypes that Vine inflated. Oakley told me, “On YouTube, when you mess up, the big creators feel a responsibility to call you out on it. On Vine, no one does.” But he added that he felt for Grier: “It would suck to have that big an audience when you’re still growing up and trying to figure out who you are.”

At the pool, three of Bach’s Vine friends practiced the weave with a sneaker on dry land, jumping up to catch and toss it. Then the trio tried it over the pool with the iPhone rolling—and Klarity dropped the J. “You had one job!” Bach cried. On the second take, to everyone’s surprise, it worked perfectly. Klarity even pulled off a three-sixty in midair as he made the no-look pass back to Bach. When Klarity got out of the pool, he flexed: “Jordan, Game Six!”

Then he shot Bach getting his J back and pushing Johns’s face aside in triumph. “Do the emotion stronger so it reads more in slo-mo, for the Instagram version,” he suggested. After doing a take of even buggier-eyed astonishment at the return of the prodigal shoe, Bach played the shot back and smiled. It had all taken only two hours. DaSilva, the neophyte Viner, noticed how, even though there seemed to be a lot of hanging and chilling, Bach kept driving everyone “until he got exactly what he wanted.”

“Now,” Bach said, “we just need one last shot of the black guys dead in the pool.”

At VidCon, teen-age girls clustered by wall outlets in pairs, watching videos together as they recharged their phones. Midway through the conference, I chatted with Addie Huneycutt and her friend Emma Hinkley, both sixteen, who had flown in from Dallas and were recharging in a corridor of the Marriott Hotel, next to the convention center. Emma was describing their favorite YouTubers as “super positive, but not fake,” when fangirl yells erupted in the courtyard. Addie cried, “Oh, my God!” Nash Grier and Cam Dallas stood in the doorway, costumed as slices of bread. Then they raced by, laughing, with a hundred screaming girls in pursuit.

Adults who don’t have teen-age children have trouble grasping how famous Nash and Cam are. Brian Robbins at AwesomenessTV—a former child star on the eighties sitcom “Head of the Class”—was just one of many M.C.N. execs who recently bid for the pair, hoping to turn them into movie stars. “It was a heated negotiation,” Robbins told me, “and in the middle of it I was eating with my sons”—Miles, sixteen, and Justin, fourteen—“at the Brentwood, and I said, ‘Justin, do you know who Nash Grier is?’ He said, ‘Every person in my school knows who Nash Grier is.’ I walked out of the restaurant, called the office, and said, ‘Close the deal.’ ”

Once Addie had calmed down and examined the fifteen photos she’d snapped as Cam and Nash pelted past, she pointed out that the mob’s behavior was self-defeating: “That blood-curdling, loud-as-you-can-scream scream just makes them run faster.” Addie and Emma agreed that they were over Cam and Nash since they released a “What Guys Look For in Girls” video (which they later deleted). In it, Cam warns, “You can’t be better than me” at video games, and Nash counsels, “Be yourself, personality-wise and appearance-wise,” but also “Shave, brush your teeth, shave. . . . Just wax, shave!” Emma said, “These are people who are literally just us—so, if they’re not sincere, why should we watch?”

The sincere disrupters of YouTube, running toward traditional stardom, fear being overtaken by the flippant disrupters of Vine. Shane Dawson, a leading vlogger, said, “They give Vine stars movies. What? If you put all their content together, it’s three minutes. Vine makes me kind of sad—I’m nervous that will turn into what content is.” Dawson, who aspires to be a great director, adheres to the traditional hierarchy, with movies at the top, then TV. Last year, when he sold a pilot called “Losin’ It” to NBC, about his days working at Jenny Craig, he vlogged that, even if the show never airs, “I can still say, ‘I’m not just that guy that puts on wigs on the Internet. I’ve actually sold a show to television.’ ” (NBC later dropped the project, but Dawson recently shot a movie that was released on iTunes.)

When Jeffrey Katzenberg or NBC execs acquire a digital talent like Dawson, they’re hoping to acquire more than a cloud of Twitter followers: they’re hoping that exposure to that star on YouTube or Vine is the gateway drug that will lure teen-agers toward the Schedule 1 rush of seeing him on “Two and a Half Men.” But while Hollywood drives toward creating shows, the digital world drives toward creating personalities. Benny Fine, who with his brother Rafi has long produced YouTube videos—they’re often called the “grandparents” of the platform—told me that, because the young expect all-access, all the time, “it’s going to be more and more important for NBC to feel like a person, to give up the mystique of having distance.” Rafi interjected, “What if the head of NBC did what we do twice a month—opened mail on camera and said, ‘This is what we have coming up’?”

Increasingly, though, it’s not the traditional world that’s becoming more like YouTube but the digital world that’s generating hybrid forms: the Web series that might migrate to a network, such as Comedy Central’s “Broad City”; the less-than-a-million-dollar movie starring a Viner that lives on iTunes. Next week marks the online début of “Expelled,” a film starring Cam Dallas, which is basically “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off” for an audience too young to have seen “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.”

YouTube’s Hannah Hart made a video-on-demand film with two other vloggers, “Camp Takota,” and she’s poised to make another. Yet Hart, whose wisecracking “My Drunk Kitchen” videos have established her as what she calls “the fun aunt of YouTube,” told me she was determined to stick with the platform that made her: “I want to build something an inch wide and a mile deep, a brand of reckless optimism. Traditional media companies would tell me, ‘Be sexier!’ or ‘Be gayer! Title all your videos “Lesbian Love Liplock!” ’ But I don’t need all of America.”

Robert Kyncl, at YouTube, explains that the digital empire, even as it grows, will remain an archipelago of tiny kingdoms. “In the disconnected world”— non-interactive traditional media—“you found a lot of casual fans who knew a little bit about someone like Kim Kardashian,” he said. “The connected world is another place, a world of unlimited shelf space and endless fragmentation, where super-fans know everything about the people they care about. In the future, there will be less overlap, less knowing the same stars everyone else knows. PewDiePie has thirty-two million subscribers—and most people have never heard of him.”

The day after shooting the Jordan Vine, Bach edited it, layered in the chorus from Nicki Minaj’s “Save Me,” and added an audio-sampled bruh—this summer’s sound effect for falling or failing—over the dead guys in the pool. He packed in eight shots, which made watching the Vine a complex and satisfying experience, but one so dizzying it was impossible to simultaneously grasp the story, the emotional arc, all three black stereotypes, and the final joke. He had reached a Francis Ford Coppola-style inflection point beyond which only mannerism could follow. More practically, viewers would have to loop the Vine at least six times to take it all in, driving up the indices of Bach’s popularity. He titled it “ALWAYS Save the J’s,” then tagged Marcus Johns and his friends who did the weave. Armaniche DaSilva went uncredited. “I only tag the most famous guys,” Bach explained. “He was an extra.”

Within an hour of its posting, the Vine had garnered thirty-two thousand likes. After waiting three more hours, to whet interest in his director’s cut, Bach uploaded a fifteen-second version to Instagram. “If it gets six thousand likes in four minutes, that’s good,” he said. “Eight thousand is epic.” The likes clocked in at 8,115. “Now I’ll upload it to Facebook, get those views, and fans put all my Vines on YouTube—it’s too much work for me to upload them—which gets me ten to fifteen K a month from the ads.” By expertly tuning every knob on the digital mixer of himself, Bach made the video one of his top three ever. On Vine alone, it’s been viewed forty-one million times.

Bach called Jarre and got a quick Snapchat tutorial. “Vine is all the same jokes now, and there’s a lot of hate,” Jarre said, sounding weary of the crass aftershocks that inevitably follow a creative upheaval. “I’m thinking of creating the next big platform after Snapchat—one where creativity comes first, not money.”

“Hit me back when you do that,” Bach said. After hanging up, he filmed himself snoring, then springing to life. But when he sought to splice these snippets into a “Welcome to Me” Snapchat he got bogged down by all the messages already coming in on the app from fans out there somewhere. “There’s so much of it!” he said. Then his face cleared. “Maybe if I’m just the one sending out the messages, and I ignore all the people trying to reach me, maybe that’s the way to go. Yeah, O.K., I got it.”

Close